Nestled along the border between China and North Korea, the vibrant city of Yanji in Jilin Province offers a unique culinary crossroads where Chinese and Korean flavors intertwine. For travelers and food enthusiasts navigating this gastronomic landscape, understanding the bilingual menus becomes an essential part of the dining experience. The Chinese-Korean menu comparison reveals not just linguistic differences but cultural nuances that make Yanji's food scene truly special.

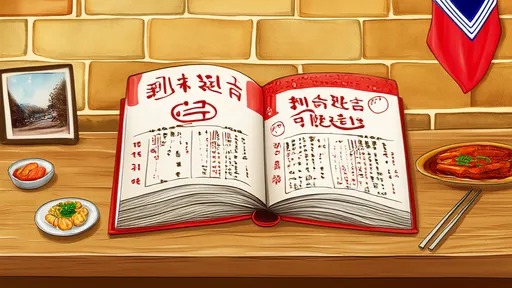

The first thing visitors notice when entering Yanji's restaurants is the prevalence of dual-language menus, often written in both Chinese characters and Korean hangul. This bilingual presentation reflects the city's demographic makeup as a hub for China's Korean ethnic minority. While many assume the translations would be straightforward, the reality is far more interesting. Some dishes maintain nearly identical names across both languages, while others undergo complete transformations that hint at deeper cultural adaptations.

Cold noodle dishes provide an excellent starting point for understanding these menu dynamics. What appears as "冷面" (lěngmiàn) in Chinese transforms into "냉면" (naengmyeon) in Korean - nearly identical phonetic translations for the same buckwheat noodle dish served in an icy broth. This similarity extends to other noodle dishes like "炸酱面" (zhájiàngmiàn) and "자장면" (jajangmyeon), showing the shared culinary heritage. However, the preparation methods often differ slightly between Chinese-Korean and North Korean versions, with the former sometimes incorporating local ingredients.

Meat dishes reveal more pronounced differences in naming conventions. The famous Korean barbecue that appears as "烤肉" (kǎoròu) in Chinese becomes "고기구이" (gogigui) in Korean menus. While both refer to grilled meat, the Korean term specifies it's meat ("gogi") being grilled, whereas the Chinese version uses a more generic term. This pattern continues with "锅包肉" (guōbāoròu), a sweet and sour pork dish that's called "탕수육" (tangsuyuk) in Korean - completely different names for essentially the same dish.

One particularly fascinating aspect of Yanji's bilingual menus is how certain dishes have developed localized identities. "石锅拌饭" (shíguō bànfàn), known as "돌솥 비빔밥" (dolsot bibimbap) in Korean, maintains its stone pot presentation but occasionally features Chinese-influenced ingredients in Yanji's version. The Korean name emphasizes the stone pot ("dolsot") and mixed rice ("bibimbap"), while the Chinese name literally describes "stone pot mixed rice." This slight variation in emphasis reflects how the dish has been adopted while maintaining its core identity.

Soup dishes demonstrate another layer of complexity in menu translations. What's listed as "大酱汤" (dàjiàng tāng) in Chinese becomes "된장찌개" (doenjang jjigae) in Korean - both referring to fermented soybean paste stew but with different connotations. The Korean term specifies the type of jjigae (stew), while the Chinese version simply calls it a soup ("tāng"). Similarly, "明太鱼汤" (míngtài yú tāng), made with pollock, is called "북어탕" (bugeotang) in Korean, showing how specialty ingredients maintain their Korean names even in Chinese translations.

The beverage section of menus offers some of the most straightforward translations, with Korean alcoholic drinks like "막걸리" (makgeolli) often appearing as "马格利酒" (mǎgélì jiǔ) in Chinese - direct phonetic borrowings. However, traditional Chinese teas might appear with their standard Chinese names without Korean translations, highlighting how each culture maintains its drinking traditions even in this blended culinary environment.

Street food and snacks present another interesting dimension to the bilingual menu phenomenon. Items like "打糕" (dǎgāo), a pounded rice cake, are called "인절미" (injeolmi) in Korean, showing completely different naming approaches. The Chinese name describes the preparation method ("pounded cake"), while the Korean name is the traditional term for the sweet rice cake coated with bean powder. This contrast appears frequently in snack items, where Chinese names tend to be descriptive while Korean names preserve original terminology.

Seasonal specialties demonstrate how Yanji's menus adapt to changing availability while maintaining cultural connections. The winter favorite "冻梨" (dònglí), or frozen pear, appears as "동배" (dongbae) in Korean menus - another case of phonetic similarity. However, summer dishes like "冷面" (lěngmiàn)/"냉면" (naengmyeon) might include seasonal variations that are described differently in each language, with Chinese menus possibly emphasizing cooling properties while Korean versions focus on traditional preparation methods.

Dessert menus reveal perhaps the most creative translations. What's known as "糖饼" (tángbǐng) in Chinese - literally "sugar pancake" - becomes "호떡" (hotteok) in Korean, a term that doesn't directly translate but refers to the same sweet stuffed pancake. This shows how some culinary concepts have been fully adopted into Korean cuisine with distinct names, while Chinese menus maintain more descriptive labeling.

The phenomenon of Chinese-Korean menu comparisons in Yanji extends beyond mere translation - it represents an ongoing culinary dialogue between two cultures. Some restaurants might list hybrid creations that don't exist in either traditional cuisine, appearing with newly coined names in both languages. These innovations reflect Yanji's unique position as a cultural bridge, where chefs freely borrow techniques and ingredients from both sides of the border.

For travelers navigating these bilingual menus, understanding these patterns enhances the dining experience. Recognizing that some dishes have nearly identical names while others differ completely helps in making informed choices. Moreover, noticing which dishes maintain their Korean names in Chinese translation can indicate specialties that the restaurant takes particular pride in or that have strong cultural significance.

Yanji's Chinese-Korean menu comparison ultimately tells a story much richer than simple linguistics. It reveals how food serves as a living connection between cultures, adapting while maintaining roots, borrowing while preserving identity. The bilingual menus act as edible maps charting the history of cultural exchange along this fascinating border region, inviting diners to taste not just dishes but the very process of culinary evolution itself.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025