In the realm of culinary experiences, color serves as a silent yet powerful communicator, shaping perceptions, evoking emotions, and even dictating cultural norms around food. The psychology of food colors transcends mere aesthetics, weaving a complex tapestry of symbolism, tradition, and biological responses that vary dramatically across cultures. While some hues universally signal ripeness or danger, others carry deeply ingrained meanings that can either whet the appetite or warn of taboo, making the dinner plate a fascinating canvas of cultural expression.

Consider the color red, a shade that often commands attention on a global scale. In many Western societies, red is associated with passion, energy, and excitement, frequently used in branding for fast-food chains to stimulate appetite and convey a sense of urgency. Tomatoes, apples, and strawberries in vibrant red are perceived as ripe, sweet, and inviting. However, this fiery hue takes on a more nuanced role in Eastern contexts. In China, red symbolizes luck, prosperity, and celebration, making it a common feature in festive dishes during events like the Lunar New Year. Yet, in some parts of Africa, red can be linked to blood or danger, occasionally causing hesitation around reddish foods unless they are traditional staples, like certain stews or meats.

Green, the color of nature and freshness, generally promotes a sense of health and vitality worldwide. In Western health-conscious circles, green vegetables like spinach and kale are celebrated for their nutritional benefits, often featured in salads and smoothies. This association extends to many parts of Asia, where green teas and leafy vegetables are staples believed to promote balance and well-being. However, in some cultures, green can also evoke ambiguity. In Indonesia, for instance, green is sometimes associated with poison or the supernatural, leading to cautious attitudes toward intensely green foods that aren't naturally occurring, such as artificially colored snacks. Meanwhile, in Middle Eastern cuisines, green herbs like parsley and mint are revered not just for flavor but for their symbolic ties to paradise and renewal in Islamic traditions.

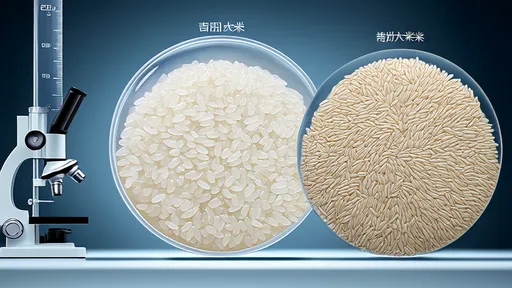

White foods often convey purity, simplicity, and cleanliness, a perception shared across numerous cultures. In Japan, white rice is a sacred staple, representing purity and essential sustenance, central to every meal. Similarly, in Western contexts, dairy products like milk or yogurt are viewed as wholesome and neutral. Yet, white can also signify absence or mourning. In parts of East Asia, white is the color of funerals and is avoided in celebratory meals, whereas in some African cultures, white foods like cassava or yam are everyday comforts but might be considered bland if overemphasized without colorful accompaniments.

Yellow and orange hues typically radiate warmth, happiness, and energy, often linked to sunshine and tropical abundance. In many societies, these colors appear in citrus fruits, carrots, and spices like turmeric, promoting optimism and appetite. In India, saffron's golden-yellow holds sacred significance in Hinduism, symbolizing purity and spirituality, and is used sparingly in festive dishes. Conversely, in some Latin American cultures, yellow might be associated with caution or illness if overly prominent in non-traditional foods, though naturally yellow items like corn or plantains are beloved staples. The brightness of these colors generally enhances their appeal, but artificial yellows can sometimes be viewed with skepticism in health-focused communities.

Black and brown colors in food present one of the most striking cultural divides. In Western contexts, these shades often denote burning, decay, or undesirability—think of burnt toast or overroasted meat—leading to a general aversion unless associated with luxury, like truffles or dark chocolate. In contrast, many Asian cultures embrace dark hues as signs of sophistication, fermentation, or healing. For example, in Korea, black beans and sesame are prized for their health benefits, while in China, black vinegar and fermented sauces are culinary treasures. Similarly, in various African cuisines, deeply browned stews and roasted meats are comfort foods rich in tradition, challenging the notion that dark colors are unappetizing.

Purple, a color historically tied to royalty and rarity, carries mixed messages in food psychology. In Western societies, purple foods like eggplants or grapes are often seen as exotic and nutritious, thanks to antioxidants. However, in some cultures, purple can be unnatural or unsettling if not familiar; for instance, in certain Southeast Asian communities, intensely purple dishes might be approached with curiosity rather than immediate acceptance. Yet, in Japan, purple sweet potatoes are a delicacy, and in Peru, purple corn is used in popular beverages, showing how familiarity breeds appreciation.

Beyond these primary colors, cultural context can transform even the most neutral shades into symbols of desire or distaste. Blue, for instance, is notoriously unappetizing in many parts of the world due to its scarcity in natural foods and associations with mold or poison. Yet, in some modern culinary trends, blue is used creatively to evoke mystery or novelty, highlighting how globalization is shifting perceptions. Similarly, metallic colors like gold or silver are universally tied to luxury and celebration, often appearing in festive foods across cultures, from Indian sweets adorned with edible silver leaf to Western desserts with gold dust.

The interplay of color and culture in food psychology underscores that there are no universal rules—only patterns shaped by history, environment, and belief systems. What one culture deems inviting, another might reject, revealing how deeply our palates are educated by tradition. As the world becomes more interconnected, these color associations are evolving, blending ancient symbolism with contemporary trends. Yet, the power of color to influence appetite and cultural identity remains undiminished, reminding us that eating is as much a visual and psychological experience as it is a nutritional one.

In summary, the psychology of food colors is a rich, dynamic field where biology meets culture. From the passionate reds of celebration to the ominous blacks of misconception, each hue tells a story that transcends the plate. Understanding these nuances not only enhances culinary appreciation but also fosters cross-cultural respect, revealing how something as simple as color can unite or divide us at the dining table. As we explore global cuisines, keeping an eye on these colorful narratives can transform every meal into a deeper journey of discovery.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025