For centuries, the term terroir has been intimately associated with the world of wine. It is a concept so deeply ingrained in viticulture that to speak of wine without acknowledging its influence is almost unthinkable. The word itself evokes images of sun-drenched vineyards, specific slopes catching the afternoon light, and the unique mineral composition of soils that seem to impart a mysterious, indelible signature onto the grapes. It is the romantic, almost mystical explanation for why a Pinot Noir from Burgundy tastes fundamentally different from one grown in Oregon or New Zealand. This profound connection to place is the very soul of fine wine. However, to confine the concept of terroir solely to the vineyard is to overlook its vast and fascinating applications across the entire culinary and agricultural landscape. Terroir is not a proprietary secret of the winemaker; it is a universal language of the earth, spoken by every plant, every animal, and every artisan product that draws its essence from a specific patch of ground.

The classic definition of terroir encompasses the complete natural environment in which a particular product is produced. This includes factors such as climate (sunlight, temperature, rainfall, wind), topography (altitude, slope, aspect), and soil (geology, biology, chemistry). Yet, it also extends to the human element—the traditional knowledge, farming practices, and cultural techniques passed down through generations that work in harmony with these natural factors. It is this inseparable combination of the physical and the cultural that creates a sense of place detectable in the final product. While a grapevine might be the most sensitive and celebrated translator of this language, it is far from the only one. A myriad of other foods and beverages are eloquent speakers of terroir, telling the story of their origin with every nuance of flavor, aroma, and texture.

Perhaps the most direct parallel to wine can be found in the world of spirits. Consider Scotch whisky. The character of a single malt is a direct conversation between the barley, the water, the peat, and the sea air. The water, sourced from local burns running over granite or heather-clad hills, carries distinct mineral qualities. The peat, cut from specific bogs, imparts a smoky, phenolic signature that varies dramatically from Islay to the Highlands. Even the humid, salty air of a coastal distillery influences the aging process as the whisky breathes in and out of the oak casks, a phenomenon often called the "angel's share." This is terroir in a glass, every bit as complex and region-specific as any Grand Cru wine. Similarly, artisanal tequila and mezcal are deeply tied to the highlands of Jalisco or the valleys of Oaxaca. The type of agave, the volcanic soil it grows in, the amount of sun it receives, and the traditional pit-roasting methods all contribute to a final spirit that is a pure expression of its Mexican origin.

Moving beyond beverages, the influence of terroir is starkly evident in the realm of cheese. This is a product where the concept of goût de terroir (taste of the earth) is literally palpable. The milk from which cheese is made is a direct product of the land. Cows, goats, and sheep grazing on specific pastures consume a diverse array of grasses, herbs, and flowers. The unique microbiome of that pasture, influenced by soil and climate, is reflected in the milk's composition. This is why a Gruyère from the summer alpine pastures of Switzerland tastes different from the same cheese made in the winter when the animals are fed on hay. The famous Roquefort cheese is legally required to be aged in the natural Combalou caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, where the specific penicillium roqueforti molds floating in the air are essential to its unique character. The animal's diet, the breed, the bacteria in the aging environment—all are threads in the terroir tapestry.

The humble coffee bean is another powerful vessel for terroir. Known in the industry as "origin character," the combination of altitude, rainfall, soil type, and processing method creates a stunning diversity of flavors. An Ethiopian Yirgacheffe, grown at high altitude in mineral-rich soil, might express bright notes of citrus and jasmine. A Sumatran Mandheling, processed in a humid climate, often develops deep, earthy, and spicy characteristics. Connoisseurs do not just drink coffee; they travel to the highlands of Guatemala or the slopes of Mount Kenya with each sip. The same is true for tea, perhaps even more so. The concept of terroir is paramount in tea cultivation, especially for revered varieties like Chinese Longjing or Taiwanese Oolong. The mist, the morning fog, the angle of the sun on the hillside—all these minute environmental details are captured in the leaves, influencing the complexity of the brew, its aroma, and its lingering aftertaste, known as hui gan.

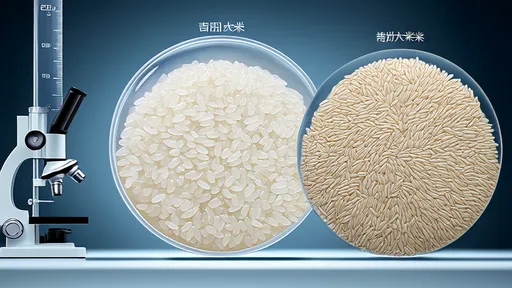

This expression of place is not limited to processed goods. It is the very foundation of all agriculture. Heirloom tomatoes grown in the dry, sun-baked soil of Sicily develop a sweetness and intensity that a greenhouse tomato in Norway could never replicate. The specific conditions of the Pacific Northwest are ideal for cultivating certain apple varieties with a perfect balance of sugar and acidity. Idaho potatoes, Vidalia onions, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, and Parma ham—all these protected designation of origin (PDO) products are official recognition of the irreplicable link between the product and its terroir. It is the reason why a chef will proudly list the farm or region on their menu; they are not just naming a source, they are describing a flavor profile dictated by nature itself.

Even the world of chocolate has embraced terroir with open arms. Craft chocolate makers, much like winemakers, now speak of "bean-to-bar" production and single-origin cacao. Cacao beans from Madagascar are renowned for their vibrant red fruit and citrus notes, while beans from Venezuela might offer deeper, nuttier, and caramel-like flavors. The soil composition, rainfall patterns, and even the native yeasts that kickstart the fermentation process of the cacao beans all contribute to these profound differences. To taste two single-origin chocolates side by side is to take a journey across continents without leaving your kitchen.

Ultimately, understanding terroir as a universal principle enriches our experience of food and drink. It transforms a simple act of consumption into an act of connection. It connects us to a specific place, to the climate that weathered a landscape, to the soil that nurtured a plant, and to the culture and people who cultivated it with care and tradition. It is a story of origin in every bite and sip. It encourages mindfulness, seasonality, and a deeper appreciation for the incredible diversity our planet has to offer. It argues against homogeneity and for the celebration of uniqueness. So, the next time you savor a piece of cheese, sip a craft spirit, or bite into a fresh fruit, pause for a moment. Consider the journey it took. Try to taste the sun, the rain, the soil, and the wind. You are not just tasting a product; you are tasting a place. You are experiencing terroir.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025